Mediterranean architecture is not a style, it is a responsibility

- inspiration

- /

- tales

- /

In our view, to create good architecture it is essential to rethink projects from a local perspective that responds to the climatic characteristics of the place where they are built. This is even more important in today’s globalised and delocalised world, marked by a climate crisis such as the one we are experiencing.

We are interested in vernacular architecture because it speaks of roots and specific places, and helps to build awareness of a territory by adapting to its climate, culture, and resources. And we are especially interested in Mediterranean architecture because it is the architecture to which we are connected both geographically and emotionally.

It goes without saying that it makes little sense to build, in València for example, a fully glazed building that requires large amounts of external energy and heavy technological systems to be air-conditioned and provide comfort. Just as it would not be logical to build such a building in Oslo with large overhangs designed to create shade, when what is actually needed there is to maximise daylight.

This may seem obvious, but unfortunately it still is not. Around us, we see buildings with thin façades, no solar protection, or façades resolved in the same way regardless of their orientation. And not only buildings from past decades, when climate awareness was limited, but also contemporary projects that, despite complying with technical regulations, have been designed in a delocalised way, detached from their immediate context.

Mediterranean architecture is an “onion” architecture

Defining Mediterranean architecture therefore refers to vernacular architecture—just as vernacular architecture takes different forms in different places. Mediterranean architecture is a concept as broad as the region itself, yet across Mediterranean architectures there are shared characteristics that reveal similarities, largely related to ways of living and to how buildings open or close themselves to the outside.

One of the strongest characteristics of Mediterranean architecture, in our view, is the way it shelters and embraces the people it hosts. Its multiple and varied layers regulate the sensations we seek to achieve: thick layers provide thermal inertia, while thinner layers protect from the sun. It is an “onion-like” architecture, where layers are added or removed depending on needs.

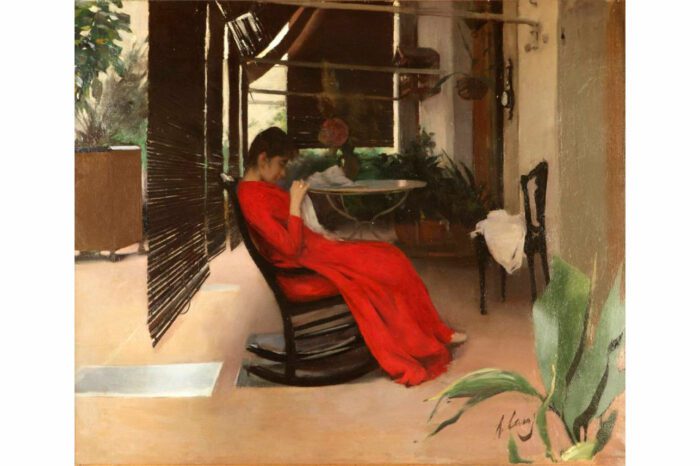

Another key feature of Mediterranean architecture is the presence of intermediate spaces—galleries, porches, or balconies—which are often ambiguous and difficult to define as strictly interior or exterior, as they function as transitions between the two. In addition to helping to mitigate and control high or low temperatures, these spaces encourage social interaction and conversation, allowing Mediterranean life to continue outdoors in summer and sheltered in winter.

In València—once again focusing on the immediate context in which we usually work—the average annual temperature is 18°C, and we enjoy more than 300 days of sunshine per year. It may sound like a slogan, but it is our reality and a privilege we can take advantage of. Designing from this context, therefore, is not an aesthetic choice but a logical and conscious response to the place we inhabit.

Mediterranean architecture is not a cliché

Mediterranean architecture is not about filling spaces with raffia, turquoise blue, roof tiles, or whitewash. This accumulation of clichés is something we must move beyond. We understand the Mediterranean as an analytical tool from which to reinterpret local popular architecture—learning from its logic and virtues, distinguishing what works and what does not, and taking advantage of its strengths without falling into mimicry.

We are not talking about specific materials, but about an honest, simple, and unpretentious architecture capable of being reinterpreted from a contemporary perspective.

Speaking about Mediterranean architecture today does not mean reproducing a folkloric image of the south or resorting to a catalogue of formal resources. It means understanding the Mediterranean as a material and atmospheric culture—a way of thinking about space through climate and time.

Architectural projects conceived from a contemporary Mediterranean perspective allow design to be understood as a tool for preserving local culture, promoting sustainability and respect for the environment, and establishing a continuous link between past, present, and future.

Mediterranean architecture is a way of building and inhabiting based on proportion, light, shadow, and the relationship between interior and exterior. It can even update its construction systems and adopt industrialised solutions while remaining Mediterranean, as long as it maintains clear conceptual principles and a deep adaptation to its environment.

Piano Piano Studio: a Mediterranean practice

place and with those who inhabit it. We observe orientation, climate, and the paths of light. Sometimes we work with natural materials; other times with contemporary technical solutions. But always with an understanding of how a space is inhabited, illuminated, and experienced.

Our practice advocates for constructive common sense, economy of means, and the pursuit of comfort through passive strategies—whether through a lime wall or a metal screen that refers to a contemporary solution.

In our projects, tradition is understood as a framework of references, an imaginary, rather than a formal repertoire. Thus, the courtyard typology becomes a strategy for light and climate, while thermal mass and the multiple layers that make up envelopes and roofs contribute to energy balance.

All of this is far from nostalgia: it is not about recovering an image of the past, but about learning from an internalised constructive intelligence that has long responded with simplicity and common sense. This is the logic that interests us—the one that seeks comfort through the essential, that uses vegetation and built shade as materials in themselves, and that understands time as part of the process that transforms architecture.

This is how we understand our practice: an architecture that does not imitate tradition, but dialogues with it; that adapts to the present without losing the memory of place, and remains distant from passing trends.